NBA superstar Kawhi Leonard sued Nike for copyright violations over the “KL2" logo. Porter Wright’s Richard Mescher sees the case as a good way to understand trademarks v. copyright rights and suggests some contract tips to avoid disputes.

During the 2019 NBA Finals in June, Kawhi Leonard, at the time of the Toronto Raptors, filed a lawsuit against Nike, accusing the corporation of fraud in its copyright application for the “KL2" logo, of which Leonard claims he is the sole author of. The case offers a good opportunity to understand trademark versus copyright rights and a look at possible outcomes.

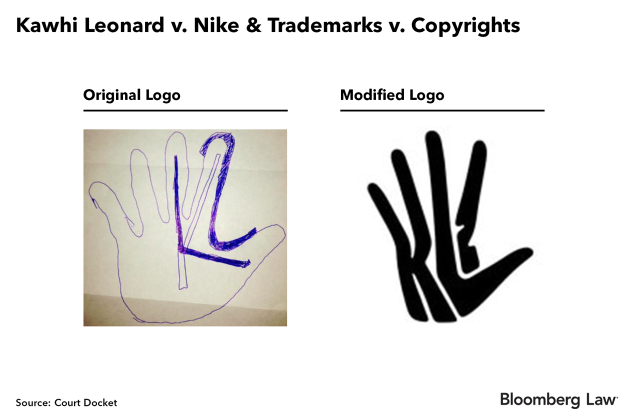

Leonard claims he created the logo in 2011 just after being drafted by the San Antonio Spurs. Upon his partnership with Nike and with no written agreement in place other than an endorsement contract, Nike helped Leonard create a new modified logo, and both began using that new logo for personal promotions and on merchandise respectively. It wasn’t until their endorsement contract ended and Leonard entered a surprise agreement with New Balance that, not surprisingly, the “KL2" logo became an item of contention.

In December 2018, Nike claimed they owned the logo according to their copyright registration and demanded that Leonard cease use of the logo on any non-Nike merchandise. Leonard, previously unaware that Nike had a copyright for the logo, responded that he intended to use the logo for future merchandise and personal gear, according to his own trademark registration.

Trademark vs. Copyright

Trademark rights are established automatically by using a mark commercially. Formal registration is not required, but does provide certain advantages, such as enabling the owner to more easily prevent others from using the mark, or a similar one that may confuse consumers, in commercial transactions.

Leonard obtained his trademark registration for merchandise and self-promotion after claiming a ‘first use’ in 2016. Although Nike has not filed for a trademark, they have evidence of ‘first use’ as early as 2014. Because trademark rights are established by first use rather than official registration, Nike has the option to supersede Leonard’s trademark registration by filing their own trademark registration in reference to their earlier ‘first use’ date.

In comparison, copyrights are also automatically established the moment an original work of authorship is put into tangible form. Formal registration is not required, but formal registration does provide certain advantages, such as more easily enforceable rights of reproduction, distribution, and creation of modified or adjacent marks.

So even though he never registered them, Leonard obtained copyrights to the original logo the moment he drew it onto paper, which was before he entered an agreement with Nike. It was after their partnership began that Nike employees helped modify the logo, the result of which has been used by both parties and is now being claimed as copyright by Nike.

Neither Leonard or Nike have raised the trademark issue (and are instead focusing on the copyright issue) because the owner of trademark rights is prohibited from using their trademark if another party owns copyrights to any element contained within the trademarked art. In other words, the copyrights trump the trademarks.

Possible Outcomes

There are three possible outcomes to this lawsuit.

Minor Modification: For the ruling to fall in his favor, Leonard will need it to say the modifications that Nike helped create were so minor, that the “new” logo cannot be claimed as a new work of authorship by Nike. This would mean that Nike has no justification in claiming copyright to the logo. If successful in arguing this case, Leonard will own the copyrights to both the original and modified logo, and only he would be allowed to proceed to use the logo as a trademark.

Major or Transformative Modification: For the ruling to be in Nike’s favor, the modifications would have to be deemed significant enough to have created a new and original work of authorship. If successful, Nike will own the copyrights to the modified logo and only it can proceed to use the logo as a trademark.

Derivative Work: If the modifications are found to fall somewhere between the two above arguments, the modified logo will be found to be a derivative work. The owner of a pre-existing work (here, Leonard) has the exclusive right to prepare and authorize others (here, Nike) to prepare derivative works. This would mean that Nike would own the copyrights to the modified logo but not to the original logo and only it can proceed to use the logo as a trademark unless there is an express contractual provision in writing that ownership of the modified logos would be transferred to Leonard. Unfortunately for Kawhi, there does not appear to be any such a written agreement.

Lessons Learned

In comparing the images above, it would appear that Nike helped make some significant changes in creating the modified logo, so it is likely to be defined as a new authorship or a derivative work, giving Nike the upper hand in this case.

So, what should Kawhi have done differently?

First and foremost, this dispute could have been avoided if a formal written contract for logo use was entered at the beginning of the partnership. This will always be important regardless of the circumstances of the case.

Second, Leonard should have included clear terms in that written logo contract stating that he would be assigned ownership of all trademarks after the expiration of their endorsement contract. Or if he considers Nike to be a direct competitor in his future retail endeavors, he should at least have had a logo contract say that Nike would be prohibited from using the trademarks after the endorsement contract ended.

Third, and maybe less obvious, the written logo contract should have expressly addressed all relevant intellectual property rights, including both trademark rights and copyrights. By including a provision that Kawhi would own all copyrights to derivative works and new works based on the original logo, Leonard would have obtained, in a roundabout way, the right to continue using the modified logo as a trademark after expiration of the endorsement contract.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc. or its owners.

Author Information

Richard Mescher is a partner at Porter Wright in Columbus, Ohio, and his practice involves all aspects of intellectual property law and focuses on the preparation and prosecution of patent applications. He has been an adjunct faculty member of the Ohio State University Michael E. Moritz College of Law since 2006, and currently teaches patent preparation and prosecution.

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

Learn About Bloomberg Law

AI-powered legal analytics, workflow tools and premium legal & business news.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools.